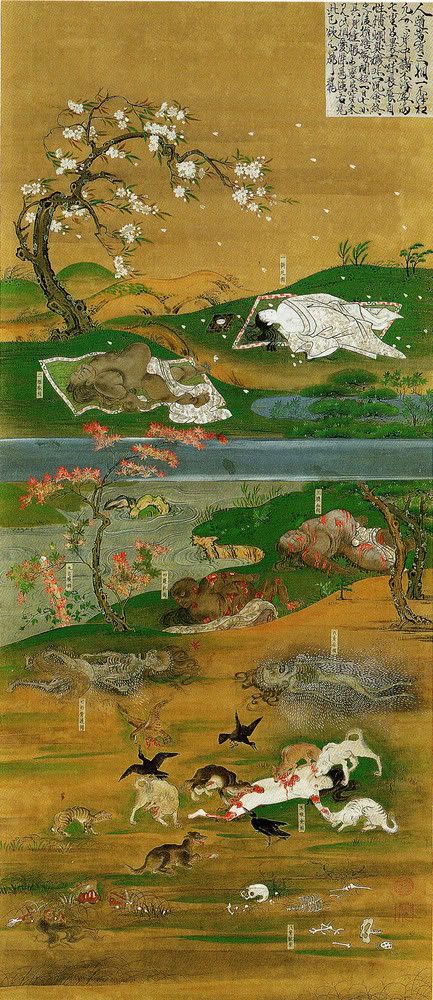

Decomposing corpse images were created from the thirteenth through nineteenth centuries in Japan. They depict the nine stages of corporeal decomposition that take place after death: recent death, bloating, rupture, putrefaction, consumption by animals, discoloration, dissolution of the flesh, fragmentation of the bones, and complete disintegration. They appear in various formats—including hanging scrolls, handscrolls, and woodblock printed books—and all images feature women, a fact that has caused some scholars to suggest that decomposing corpse images—and stories that center on the decomposition of female corpses—at the very least reveal a gendered gaze and quite possibly express the inherent misogyny of medieval Japanese Buddhist thought. (1) The two articles that I read on the subject did not dwell on this aspect of the argument however.

Gail Chin, in her essay on the topic, argues that the images actually exhibit a multiplicity of meanings. She focuses her study on how the images were intended to educate viewers of both sexes about the “frailty of human existence” and the “repulsive nature of the human body” by means of utilizing a female body as emblematic of the non-duality of Buddhist doctrine. (2) Through the process of decomposition, the female body is shown to metaphorically transcend flesh and achieve a stage of nothingness (enlightenment). The implication, Chin asserts, is that if a woman—one of the most impure and repugnant incarnations in the Buddhist cosmology—can become enlightened, so can anyone. (3)

Kanda Fusae, by contrast, argues that the images have different functions in different eras and that their relative levels of adherence to the doctrinally established progressions, as well as changes in their stylistic elements, provide clues as to what those functions were. From the early medieval to the Edo period, Kanda identifies four basic functions to which decomposing corpse images were applied: object of meditative contemplation, tool of didactic practice, meritorious offering on behalf of a deceased loved one, and handbook for the moral education of young women. (4)

While both authors are primarily focused on the relationship of the images to Buddhist doctrinal theory and temporal context, they both employ the term “grotesque” to describe the images. While Chin uses the term only once in passing, (5) Kanda repeatedly refers to the depictions of decomposing corpses as grotesque. Moreover, she associates grotesqueness with explicitness. As the images become less and less faithful to biological exactness over time, Kanda deems them less grotesque. (6) Neither Chin nor Kanda ever really fully articulate what they mean by “grotesque,” but their use of the term seems to me potentially legitimate, even though the grotesque can often refer to an entire aesthetic discourse that contemporary producers of decomposing corpse images would have known nothing about.

The meaning of the word grotesque today has diverged considerably from its original meaning, and an exploration of its etymological origins lies well outside the scope of this essay. (7) By the nineteenth century, a number of different interpretations of the grotesque proliferated and the much-studied theories of John Ruskin are among the most important of those. (8) In contrast to Walter Bagehot, who viewed the grotesque as something that arose involuntarily in nature, (9) Ruskin considered the grotesque to be a deliberate product of artistic volition that could be either noble or ignoble depending upon the moral character of the artist in question. The greatest example of the grotesque, in Ruskin's view, arose from the serious confrontation of the unexplained horrors of the world. For Ruskin, the honest contemplation and rendering of those terrors that man cannot comprehend had the potential to ennoble. They were, in a sense, didactic.

It's certainly tempting to think about Japanese images of decomposing corpses in the Ruskinian context. Both Chin and Kanda argue for a "moralizing" dimension to the works, and the confrontation with a blatant depiction of death could certainly be classified as a confrontation with an incomprehensible horror—particularly in Japan, where death has always been viewed as a terrible defilement and source of taboo. Nevertheless, one particular aspect of Ruskin's philosophy makes it a bad fit for pre-modern Japanese art, and that is Ruskin's belief that artistic volition can be determined via stylistic analysis. For Ruskin, the intention of the artist is writ large in the visual elements of the art object. (10) In the pre-modern Japanese context, where artists very often worked under a director at the behest of a patron, there is no question of artistic volition. Consequently, a theory of the grotesque that eschews issues of artistic agency is preferable.

Noël Carroll, who I cited in my previous entry and for whose theories about grotesque art I have a fair degree of simpatico, defines the grotesque along very useful structural lines. His definition is based upon the supposition that the grotesque is comprised of things that violate our sense of the natural and ontological order of things. This includes fusion figures (composites), instances of disproportion, formlessness, and gigantism. Carroll's structural view of the grotesque applies only to animate beings; while a building or an idea can be metaphorically grotesque, they are not "structurally" grotesque. (11) In this conceptualization, the grotesque actually stands apart from moral concerns. It can be aligned with moral, amoral, or immoral concerns on a case-by-case basis.

This concept of the grotesque seems like a better fit for Japanese images of decomposing corpses. The experience of viewing a human body in varying stages of decay is unsettling, to say the least. The corpse represents a break with our natural expectation of human appearance; namely, that the human being will be alive. As decomposition progresses, the corpse becomes disproportionate and finally formless. The human becomes thoroughly inhuman.

However, one might argue that the process of decomposition, though unsettling, is not biologically abnormal. (The abnormality would come if the corpse sat up and started calling for brains, or otherwise behaved in an un-corpse-like manner.) One might further argue that within the context of medieval Japanese Buddhist ritual practice, the corpse actually constituted a fully natural object. Or, on the other hand, one might argue that the corpse, as a traditional object of horror, revulsion, and taboo would always have carried an unnatural—offending—connotation.

The real question, it seems to me, is not whether or not Japanese images of decomposing corpses can be called grotesque. The question is whether or not they should called grotesque. And on that point, the jury is still out.

Notes:

1) Tonomura Hitomi is one scholar who explores this possibility, albeit briefly and in the wider context of medieval Japanese literature as a whole. See “Black Hair and Red Trousers: Gendering the Flesh in Medieval Japan,” The American Historical Review 99, no. 1 (February 1994): 145.

2) The concept of non-duality holds that all things in the universe—whether animate or inanimate, in pursuit of Buddhist knowledge or no—contain the Buddha nature and therefore have the potential to achieve enlightenment. In non-duality, things usually considered to be diametrically opposed to one another (for example passion for earthly pleasures and the renunciation of such) are understood to actually be one and the same.

3) Gail Chin, “The Gender of Buddhist Truth: The Female Corpse in a Group of Japanese Paintings,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 25, no. 3-4 (1998): 277-317.

4) Kanda Fusae, “Behind the Sensationalism: Images of a Decaying Corpse in Japanese Buddhist Art,” The Art Bulletin 87, no. 1 (March 2005): 24-49.

5) Chin, 308.

6) Kanda, 37-38, 41.

7) For a thorough history of the grotesque see David Summers, “The Archaeology of the Modern Grotesque,” in Modern Art and the Grotesque, ed. Frances S. Connelly (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003): 20-46, or chapter 1 of Wolfgang Kayser’s The Grotesque in Art and Literature, trans. Ulrich Weisstein (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1963): 19-28.

8) Ruskin's ideas about the grotesque are found scattered throughout his considerable output, but two of the most valuable sources for his thoughts on the subject are found in "Grotesque Renaissance," in The Stones of Venice, Volume 3 of 1853, and "Of the True Ideal: Thirdly, Grotesque," in Modern Painters, Volume 3, Part 4 of 1856. Both are available online through Project Gutenberg and Google Books, respectively. My reading of Ruskin derives entirely from these essays.

9) Walter Bagehot, "Wordsworth, Tennyson, and Browning; or, Pure, Ornate, and Grotesque Art in English Poetry," in The Collected Works of Walter Bagehot Volume 2, ed. Norman St. John-Stevas (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965): 353.

10) Ruskin explores artistic volition via stylistic analysis at length in his evaluation of two griffin sculptures from ancient Rome and the Lombard-Gothic period. See "Of the True Ideal: Thirdly, Grotesque," 105-112.

11) Noël Carroll, "The Grotesque Today: Preliminary Notes Toward a Taxonomy," in Modern Art and the Grotesque, ed. Frances S. Connelly (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003): 291-312.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This is probably too tangential, but you might check out Linda Williams' "Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess." It's tangential because it deals with 20th-century American film, but it explores many of the issues you raise, I think. It could be a quick read if you had time. I've pasted my notes from reading it below, in case they help you decide whether it could be useful.

ReplyDeleteIn “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess,” Linda Williams explores the genres of pornography, horror, and melodrama, which have all been categorized as genres of excess. She argues that “sex, violence, and emotion are fundamental elements of the sensational effects of these three types of films, [so] the designation ‘gratuituous’ is itself gratuitous” (702). She further describes these “body genres” as ones that not only depict a bodily sensation, but also promote an identical sensation – “involuntary mimicry” – in the viewer, and that cause the viewer to lack a normal aesthetic distance from what is being experienced within the film (704-5).

Williams’ argument is again a feminist one, centering on the role of woman as passive receptor in these body genres. She argues that each of these body genres hinges “on the spectacle of a ‘sexually saturated’ female body,” as well as on the female as victim (706). She assigns a type of perversion to the spectatorship of each genre: sadism for pornography, sadomasochism for horror, and masochism for melodrama (708). These perversions relate to the viewer’s identification with the women victims and the related power structures within the films. She also explores each genre in relation to fantasy and temporality within the films (713-4). She uses these analogies of perversion and fantasy to analyze how these films and their spectatorship describe social norms and “address … cultural problem-solving” (714).

Ultimately, I found Williams’ argument far less compelling than Hansen’s. While it draws an interesting corollary among the three “body genres” and raises important questions about each, it remained theoretical and less grounded in actual instances of film and related cultural phenomena. Some of her assertions, such as those about temporality, strike me as accurate but off-topic or irrelevant, and I wish she had developed them a little more for me to see where she wanted to go with them. Because of this structure, it seemed to me more an interesting yet nebulous question raised rather than a definitive question answered. In other words, Williams has brought to our attention important issues within what she terms “body genres,” but leaves the topic very much open for future exploration.

Funny story! I came across your blog because your essay on the Winter Soldier got re-whatevered on tumblr, but I am in fact a fellow pre-modern Japanese-related graduate student. Moreover, I discovered the whole kusouzu phenomenon only last semester, from the headnote to a Saikaku story I was reading in which the (wildly misogynistic) narrator refers to the beauty of all women as being merely makeup on a kusouzu.

ReplyDelete(Which, incidentally, I don't think was Saikaku's actual position -- by all accounts he was devoted to his wife and devastated after her death, but Nanshoku Okagami was written to cater to gay dudes, so~~~~)

Anyway, keep up the good work! I liked your essay on the Winter Soldier for how it pointed out that the *one* memory they chose to feature in CA:2 was of Bucky offering help and Steve refusing to take it, which was the exact opposite of what wound up happening in the movie itself. Which was, I think, too subtle for most theatre-going audiences (and indeed, too subtle for me, and I LIKE reading into this kind of thing) but drove home a point I'd had about fans becoming makers. Because one of the major objections to JJ Abrams remaking Star Trek is that he has been AT PAINS to state in every interview that he was never a fan of Star Trek -- that he never watched it until he was hired to direct a new movie of it. And yeah, I don't doubt that he watched the previous series in advance of directing a sequel to it -- but not having been a fan of it means that he never internalized the ethos of it. Being a fan means having this kind of dialogue -- tossing back and forth interpretations of what THOSE ACTIONS mean to THIS CHARACTER, with other people who've seen the show at least as many times as you have.

And I think the Star Trek reboot has suffered for it, and the various DC movies, because they keep hiring people who DON'T. LIKE. COMIC BOOKS. ...and what do you expect to happen?

...anyway, my boyfriend is trying to learn Japanese now and my job is to be supportive and/or fill in the parts he doesn't understand, which is all of it. He's decorative.

How funny that you're a pre-modern Japanese grad, too. (There are more of us than people think... we are everywhere!) Are you in literature? I ask because of the Saikaku mention, and because I often think I should have been a literature person and I might be jealous. :-)

DeleteI think your comments on the Star Trek reboots are spot-on. In fact, while I enjoyed the potentials set up by the first film, I absolutely despised the second for a variety of reasons. (I wrote a review of it on my tumblr, if you're interested: http://sechan19.tumblr.com/post/50566840490/review-star-trek-into-darkness-spoilers ) I definitely agree that the fact that so many of these filmmakers don't like the source material is a definite problem in how the films are being made. Even more of a problem is the laziness that is implied by such an excuse. "I don't like the source material." Subtext: "And I'm not going to do my fucking job and find out anything about it to ensure that my film does its due diligence." More than anything else, to me "Into Darkness" (as a prime example) was just sloppy. It was sloppily written, and the fact that JJ Abrams didn't kick up a fuss about that indicates sloppy directing - not in technical aspects, perhaps, but in the essential groundwork. Seriously, I could go on forever about how peeved that movie made me. (I suspect that I have, actually. My father supposedly still complains about my complaints anytime he rewatches "Into Darkness"!)

Anyway, thank you for your comments - and for reading. Good luck with your work and with helping your boyfriend learn Japanese. For what it's worth, I've been learning it for ten years now, and I'm still awful at it. ;-)